In honour of Elsie Conference: Celebrating 50 years of women’s refuges in Australia

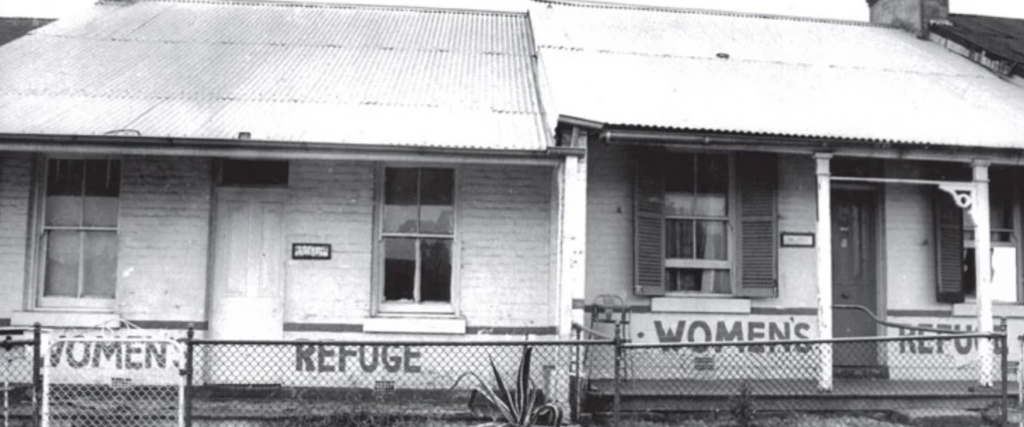

It’s been 50 years since the Women’s Liberation Movement, led by Dr Anne Summers, took residency of a vacant property on West Moreland Street, Glebe, and founded Australia’s first refuge – Elsie.

A safe haven for women and children fleeing violence, Elsie was a flagship for change, inspiring more of its kind and creating a groundswell of action around housing and support for survivors. Grounded in feminist activism, domestic and family violence was yet to be considered criminal and the signifance of Elsie extended beyond its offering of shelter and into the political and judicial spheres; bringing the private (often unspoken) abuse of women and children within the home, into the public eye. Ahead of the upcoming Elsie Conference: Celebrating 50 years of women’s refuges in Australia, we spoke to Anne about the advent of women’s specialist services, change within the sector and continuing to strive for a future that ameliorates violence against women.

Many women working in the domestic and family violence field know the story of Elsie – indeed Wesnet has retold it many times – but it is hard to appreciate what life might have been like for women experiencing violence before women’s specialist services. What did women do before the Women’s Liberation Movement and the subsequent Whitlam era reforms?

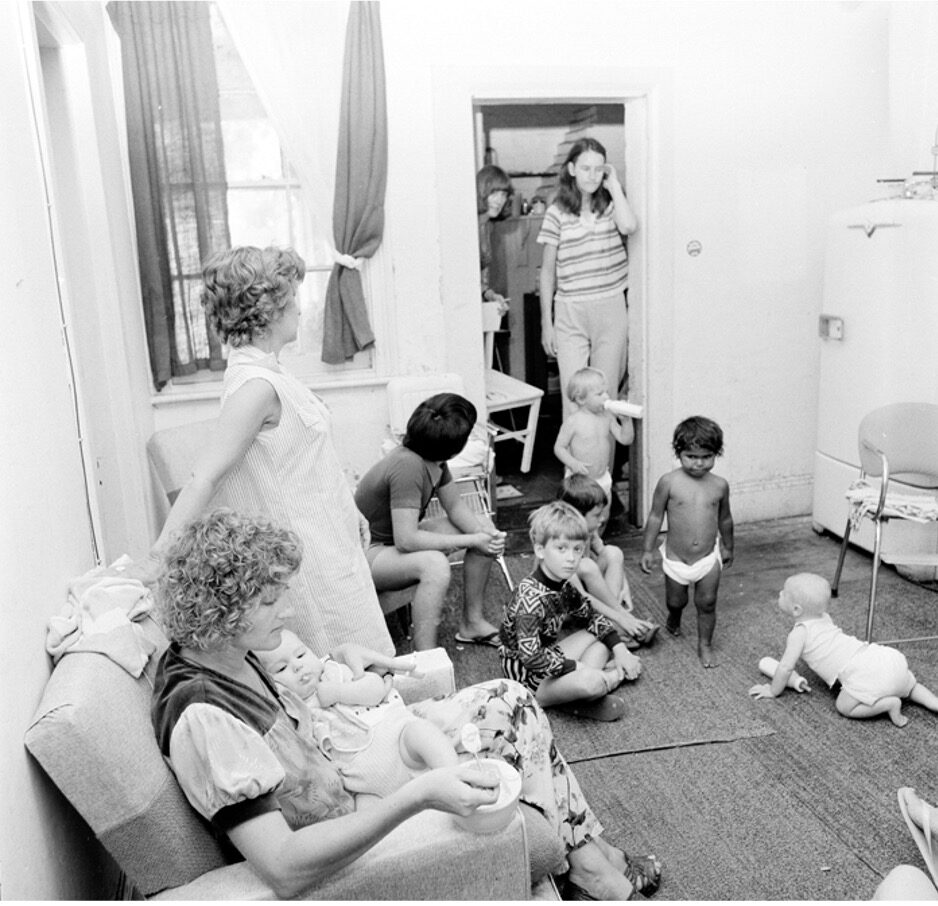

Their prospects were very bleak. I remember well when I first got interested in the idea of starting a women’s refuge (based on the one in London called Chiswick Women’s Aid run by a great woman called Erin Pizzy), I visited the existing facilities. There were two that I could find. One run by the Salvation Army and one by St Vincent de Paul. They offered dormitory style-accommodation and while they offered women and their children safety and a roof over their heads, it was for the night only. They had to vacate each morning, taking their belongings with them, and find somewhere to spend the day. Imagine trying to look after a couple of kids in the city all day while you waited for the shelter to re-open, especially if you had no money to sit in a café, or it was raining. It was this situation that made me determined that our refuge would offer 24 hour accommodation and that we would provide child-care so that women could safely leave them at the refuge if they needed to go to the doctor, or see a lawyer or go to court. We would offer a totally different experience.

Clearly the main function of women’s shelters is to get women away from men’s violence, but today’s refuges do so much more in terms of wrap-around services and prevention and recovery programs. How were those seeds sown at Elsie and other early refuges?

It was always the intention of Elsie and other early refuges to offer more than just safe accommodation, although that of course was paramount. But, as feminists, we wanted to help the women find their way forward to new lives where they could become self-reliant and not be dependent on violent men. Today’s refuges face new and greater challenges as they deal with women who come to them having suffered appalling financial abuse, often their entire savings wiped out and debts accumulated in their names they knew nothing about. Their needs are very different from the women who have suffered physical abuse. Likewise, a great many, if not most, women coming to refuges these days have been subjected to technology-enabled abuse, and all refuge conduct tech audits on women’s phones and laptops, and even on the children’s toys to ensure that no spyware has been installed. Or to get rid of it if it’s there.

It was always the intention of Elsie and other early refuges to offer more than just safe accommodation, although that of course was paramount. But, as feminists, we wanted to help the women find their way forward to new lives where they could become self-reliant and not be dependent on violent men.

Today we also talk about trauma-informed care as being central to our services – and something that often differentiates specialist services from generalist crisis accommodation – do you think that was always inherent to women’s specialist services?

I cannot speak from experience because although I was involved in the founding of Elsie I only worked there for a very short time, in the very early days before we had become aware of the complexity of issues that many women faced. The notion of the need for trauma-informed care developed later as it was realised that these complex needs had to be addressed in different ways.

We have seen some states in particular move DFV services away from smaller community-based specialist services to larger charities and corporates. What do you think are the key consequences of this (if any)?

I think this needs to be urgently investigated because we do not really know. There are all sorts of rumours but I am not sure that we have a factually-based understanding of how these large institutions operate. We have heard, for instance, that they charge women large sums of money to stay, that they are only open 9 to 5 and cannot therefore offer 24 hour emergency accommodation which was always central to the women’s refuges. I have also heard that some of these places employ men which, in general terms, does not sound like a good idea for women who are escaping trauma and abuse dealt out by men.

Funding was quick to shift from the federal sphere in the early years to be predominantly state-based (although the majority of Wesnet members also rely heavily on different federal grants and philanthropic revenue) – did this have an impact on services? What do you think is – or should be – the role of federal government in addressing violence against women?

Again, my not being continuously involved over the years, and also having lived overseas for 13 of the past 20 odd years, means I have not witnessed first-hand the impact of the many changes in funding although I can of course understand that uncertainty and inadequate funds are going to make it very difficult to deliver reliable and competent services. If we had just federal funds to rely on, we could have uniformity in terms and conditions and reporting arrangements which would make life a lot simpler.

Although the roots of DFV remain the same, we’ve seen the nature and tools of violence change over time. What do you see as the main changes? Are we responding quickly enough to the changes?

I think that the sector has perhaps been a little slow to understand that the fundamental nature of DFV is changing. We have perhaps tended to see things like financial abuse and tech-enabled violence as ancillary forms of abuse whereas now I think we are starting to understand that they have become primary forms. Perpetrators are getting the word that hitting women is not the way to go (not that it doesn’t still happen of course) but that there are more effective ways to control and punish women that are harder for the police to detect or for the women to report – especially if she is not even initially aware they are happening to her. I would argue that domestic violence must now be defined to include multiple forms of abuse from physical, sexual, emotional and controlling forms of behaviour to outright robbery and criminal surveillance. We are still learning the extent of these behaviours, let alone how to stop them. It is a huge challenge for us. But we must be firm in our conviction that this is domestic violence, this is how it has evolved. As new weapons become available it will no doubt evolve further.

I think that the sector has perhaps been a little slow to understand that the fundamental nature of DFV is changing. We have perhaps tended to see things like financial abuse and tech-enabled violence as ancillary forms of abuse whereas now I think we are starting to understand that they have become primary forms.

You’ve spent a lot of time in the United States and seen up close how quickly progress can be undone. Apart from being discerning in our voting choices, are there other things we can do to make sure that progress made in women’s equality in Australia is more resistant to hostile politics? Do women’s specialist services have a role in this?

Although the repeal of Roe v Wade and the subsequent takeover of abortion laws by punitive and restrictive states is by far the most dramatic example of the clock being turned way back, we must remember we have also experienced women’s entitlements being severely restricted, especially in employment, under the Howard government. The changes he made are still with us, with the tax system being used to discourage women from working full-time and thus earn less and have lower super balances. I could give many more examples. We have to be constantly vigilant and certainly not support any political parties that do not support women’s rights and progress generally, as well as specific issues such as our reproductive rights and the need to be free from violence.

You’ve done a lot of work around poverty, single motherhood and violence, and your work with Terese Edwards and other tireless advocates will go down as a major recent achievement for women, particularly in terms of changes to family law and welfare payments. From your perspective and experience, what are other key things that require urgent reform?

The Family Law system and the Child Support systems are both in need of major reforms and it is urgent they be addressed. I have set my sights a little lower and this year am campaigning on Let’s Finish the Job. We are urging the federal government to expand the reforms to the Supporting Parents Payment made in last year’s budget to cover all single parents until their youngest child turns 16. Last year’s budget left behind 16,910 single parents, most of them women, who together have 17,905 children and who earned $2893.40 less than single mothers whose youngest child was aged under 14. This is blatantly unfair. All single parents should be treated equality, not have some of them arbitrarily thrown onto the dole just on the basis of the age of their children. We will be working hard to get this changed in the 2024 budget.

The occupation of Elsie was a radical act at the time and will be remembered in history as a radical act. Do we need more radical acts to hasten progress or is conventional advocacy the route to reform?

We do what is necessary at the time. I think we could all be a bit braver when it comes to demanding change that would make women and children safer and less prone to live in poverty.

The Elsie Conference has been tagged ‘Celebrating 50 years of helping women and children escape domestic violence’. What should we be celebrating the most?

We will celebrate the fact that we were able to establish the women’s refuge movement and very quickly, in every state, open refuges to help women and kids. The fact we are still around is a major testament to our strength and endurance, although it is also a sad commentary on our failure to make much of a dent in the rates of violence. But as well as celebrating we will be examining our record, looking at where we could and can do better. Do we need to change our basic model? Are the new forms of DV making refuges less necessary or do they mean the role of refuges has to change? I expect a lot of lively debate around this.

Finally, what are you most looking forward to at the Elsie Conference?

To seeing everyone there, celebrating but also re-evaluating and figuring out how to do better in the future to end violence, not just pick up the pieces. I have my ideas on what we should be doing but that’s a whole other conversation!