WESNET INTERVIEW SERIES

Since 2004, Renee Dixson has been working as a human rights defender at the international and national levels.

As a result of visible work, they were forced to leave the country where they lived. The process of settling down in Australia and their position as an outsider and insiders have given them an opportunity to see how discourses shaped stories around LGBTIQ+ and refugee communities.

In recognition of the culmination of the 16 days of activism and Human Rights Day on 10 December, we were grateful for the opportunity to talk to Renee, focusing particularly on their work regarding LGBTIQ+ forced displacement and their lived experience and observations relating to human rights and intersectionality. Read the interview below.

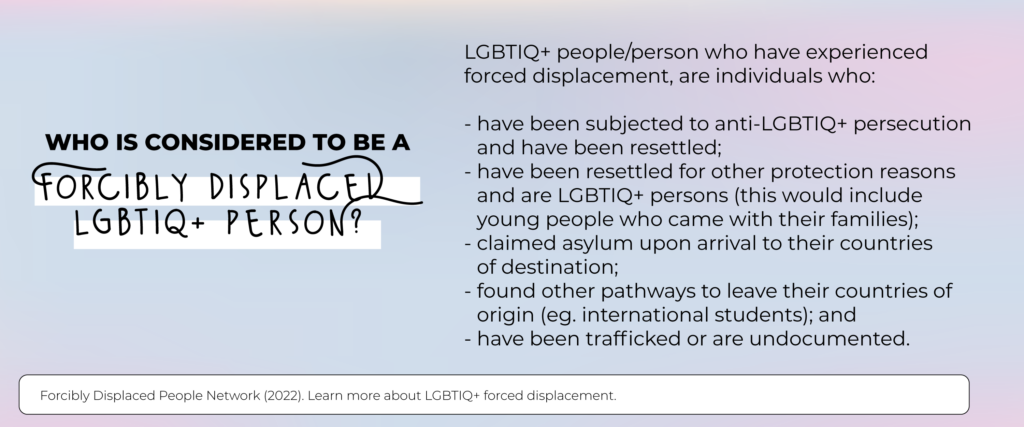

1. Hi Renee, thank you for joining us today and congratulations on your Human Rights Award nomination! Can you please tell us about the Forcibly Displaced People Network (FDPN): what does forced displacement mean, how does the network work and what are its objectives?

Forcibly Displaced People Network was born out of the lived experience of being queer and displaced. My wife and I sought asylum in Australia as LGBTIQ+ human rights activists. Despite many people telling you something like ‘it must feel so free to be queer in Australia’, there was great silencing surrounding the topic of LGBTIQ+ displaced people back then. To some extent, it continues until now.

Forcibly Displaced People Network, or FDPN for short, was established to support other LGBTIQ+ people who have been displaced to find safety and community. We work on building the capacity of LGBTIQ+ displaced people to settle in Australia. And an integral part of the success of settlement is also training for community services on inclusive and culturally competent service provision.

2. Clearly, no two stories are the same, but what tends to be some key features of the LGBTIQ+ experience of forced displacement?

This is correct, we are working with a very diverse group of people coming from many countries. What unites them is that the persecution and violence they experienced was inflicted on them simply because of who they are, who they love and what their body looks like.

What unites them is that the persecution and violence they experienced was inflicted on them simply because of who they are, who they love and what their body looks like.

What differentiates this community from those displaced people who are not LGBTIQ+ is that violence is more intense, it is ongoing and most likely, it has begun at an early age, even before people came out. The violence is inflicted by the state, but it can also come from the families, and there is little access to justice.

It is also common for displaced people to experience other drivers of displacement, such as war. What this means, then, in the settlement, is that there is little to no ethnic community and family support, there is a great distrust of authority figures, including services, and there are common experiences of isolation out of fear of discrimination.

3. Much of the work of the FDPN seems to be framed in the international context, for example, around CEDAW and the 1951 Refugee Convention. Why is this important?

There is still much resistance towards achieving equal rights for LGBTIQ+ communities. It is essential to frame this issue in the human rights context. We are talking about the rights to self-determination, freedom, life, dignity and many more.

It is essential to frame this issue in the human rights context.

It is also about intersectional approaches. We cannot achieve women’s equality without equal rights for LGBTIQ+ and refugee women, and we must talk about LGBTIQ+ people in any refugee justice work.

4. Following this thought, we’ve seen recently in Iran evidence of killings of women and women human rights defenders as well as routinely targeted harassment, hate speech, discrimination, defamation and other forms of offline and online violence to silence and punish women’s public participation and defence of their own rights. Some people say that Australians often live in a bubble, isolated from the rest of the world. How do human rights violations across the world, such as the ones currently experienced by people in Iran and Ukraine, impact us? Why is it important to be aware of these and support human rights efforts everywhere and anywhere?

There is a tendency to think we live in isolation, but we are all interconnected. You cannot say that you support human rights here and close your eyes to what is happening elsewhere.

Standing up against Russian and Iranian dictators, but also Israeli occupation of Palestine and the Taliban (unfortunately, this is not a complete list) is sending a message that there must be zero tolerance for this kind of action everywhere. Allowing those human rights violations means failing our communities.

5. Geneva and New York are a long way away – what can civil society and individuals in Australia do to encourage global cooperation to address universal issues, such as gender-based violence?

We need to have a common language and understanding. For example, in the context of gender-based violence, it is very common that LGBTIQ+ people are not included or even not seen as legitimate victims. What this does is actually a huge disservice to the whole cause.

There needs to be better and more intersectional solidarity and alliance building. There also needs to be bigger pressure on governments not to make concessions when it comes to LGBTIQ+ lives. For example, when the Global Compact on refugees was being developed, LGBTIQ+ communities were one of the first groups to be dropped from the text under pressure. Now, we have a historical document with zero mentions of this community.

6. Are there opportunities for Australia – governments and civil society – to take a stronger leadership role in advancing human rights?

We still see this segregation among issues – you either do refugee work or LGBTQ+ work, or women’s rights. Intersectionalities only come in on some international days, but there is no sustained and meaningful engagement. I think we need to learn to see the interconnectedness between all these causes and give better support because we are only stronger together.

7. At the more local level, in the domestic and family violence specialist services space, it is widely understood that violence by men against women, non-binary and LGBTIQ+ people is underpinned by gender inequality, but – at the service level – what improvements can be made? Do services need to be specially designed to meet the needs of both refugees and LGBTIQ+ people? What might these services look like?

Yes, while the drivers are the same, there are still significant differences. Violence against LGBTIQ+ people is also underpinned by homo-, bi- and transphobia.

There are many steps services can take to provide more inclusive service provision, the most important one, of course, is training to understand all the contextual information. At FDPN, we provide such training to services.

We had a case supporting a survivor who was bisexual and married to a man. When the husband found out about her sexuality, the abuse escalated. When she tried to seek help she was met by a case worker who, although she tried to be supportive and validate what had happened to her, could not pronounce the word ‘bisexual’ and struggled with the term. It made it so much worse for the survivor because it was as if the case worker also didn’t believe her sexuality was an integral part of her experience.

Other things that service providers can do to show their support are displaying LGBTIQ+ flags in their common areas (at FDPN, we sell the most beautiful posters for display), marking days of significance for LGBTIQ+ communities, and hiring LGBTIQ+ staff.

8. How can we be better supporters and allies of forcibly displaced people?

If you don’t know, learn. And when you learn, pass it on.

We have an incredible opportunity coming up: The Queer Displacements conference. This is a space to learn about supporting LGBTIQ+ forcibly displaced people for those interested. I also invite you to follow us on social media to learn more: https://www.instagram.com/fdpn.lgbtiq/

If you don’t know, learn. And when you learn, pass it on.

9. Why is it so important to record, archive, and preserve the experiences and stories of forcibly displaced people? Can you tell us a bit about your Assembling Queer Displacement Archive (AQDA) project?

The silencing and erasure that exists in society are always translated into cultural memory and institutions. Think about whose stories are always represented and whose are not, or about the specific angles we always hear from. Museums and archives are not yet places that reflect the diversity and complexity of our communities. Even when there are LGBTIQ+ archives or exhibitions, it is very common that the stories that dominate are the ones of middle-class, white, cis, gay men.

Museums and archives are not yet places that reflect the diversity and complexity of our communities.

I am developing an Assembling Queer Displacement Archive (AQDA) to counter those single narratives. Recording the diverse experiences of displacement is essential. AQDA is an online open-access archive that will collect and preserve the oral histories of LGBTIQ+ migrants and refugees. These oral histories are shared by people, and they are in full control of what they want to share.

Far too commonly, LGBTIQ+ refugees are being expected to tell particular stories: that the country of origin was barbaric and Australia is a safe haven. But this is only one and not a complete story that misses the nuance. It is important that an LGBTIQ+ displacement story is not reduced to this simplicity.

It is important that an LGBTIQ+ displacement story is not reduced to this simplicity.

AQDA is my PhD project. The archive is being built now, and I am still collecting stories, so if you are an LGBTIQ migrant or refugee, please reach out to me.

10. Why is it so important to record, archive, and preserve the experiences and stories of forcibly displaced people? Can you tell us a bit about your Assembling Queer Displacement Archive (AQDA) project?

I am expecting the archive to be launched, and it will be a live project going forward.

It can be used by policymakers and researchers in their work but also, most importantly, by the community to hear similar stories and to know that they are not alone and that there is a community out there.

—

About the series: The WESNET Interview Series brings an array of diverse opinions, perspectives and insights from different professionals, practitioners, experts, and advocates on violence against women and girls and other forms of gender-based violence. We aim to share the full diversity of voices to help inform and expand the narratives around ending violence in all its forms. Not all the voices will agree on every aspect of what to do and how to do it, but all the voices are from those committed to ending gender-based violence. You can read the rest of our interviews here.