FROM OUR NATIONAL CHAIR, JULIE OBERIN AM

Part of the feminist fabric

Women’s safety has always been at the heart of the women’s movement.

Historically women – where they were able – provided shelter to other women and, particularly, children.

Networks of resistance to the patriarchy have operated throughout time – including during the Scottish witch-hunts of the 16th century through to providing reproductive care to women in the US red States today.

Second wave feminism and women’s refuges

Throughout most of the last century, domestic violence – often minimised as ‘wife-beating’ – was still largely considered a private matter between ‘man and wife’. Women were routinely expected to manage men’s violence.

Finding shelter for women escaping domestic and family violence became a key platform and the public face of feminism in Australia during the second wave of feminism of the 1970s.

It is through the unity of women that trauma-informed and women-centred services began to exist to support women and children escaping violence.

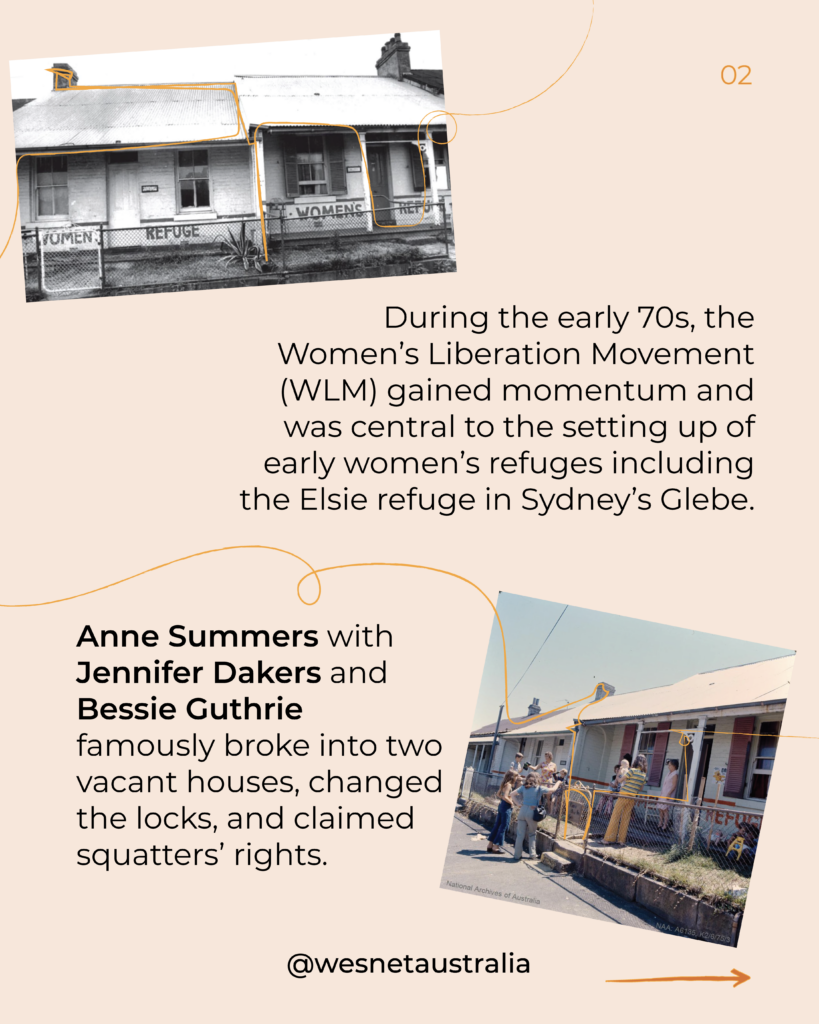

In Melbourne, the Women’s Liberation Halfway House Collective (WLHHC) opened the first Victorian women’s refuge in August 1974, in a house provided to them rent-free from an anonymous woman following an intensive letter-writing campaign. (1) Earlier that same year, in March, the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) famously broke into two vacant houses, changed the locks, and claimed squatters’ rights to open Sydney’s first women’s refuge “Elsie”.(2)

WLM, the Women’s Electoral Lobby and other women’s collectives worked tirelessly to set up refuges across the country, with many services being initially staffed by volunteers. Following the successful demonstration by the women’s movement of the need and the demand for support, the Whitlam government stepped in and provided funding in 1975, sending a strong message, not just about the need for women’s refuges but the legitimacy of the women’s movement and the centrality of safety to equality. (3)

More than a shelter

Women’s refuges saved women’s lives by giving them a place to go, away from violent men. But they also facilitated empowerment and tools for living. They helped with the skills and support to keep them away from violent men.

As Bowstead states, “Refuge spaces require, but also enable, contact and encounter between women; and communal living and group processes can enable interaction and collaboration between women. These collective processes begin to counteract the isolation of abuse and to help prepare women for their lives after the refuge.” (4)

Through the refuges, women found power in other women, both through other victim-survivors as well as the workers (many of whom were also victim-survivors).

Part of an international movement

By the 1980s and 90s in Australia, the women’s movement had been successful in that there was a general acceptance that governments bore some responsibility for women’s and children’s safety.

But there was still no integrated plan to address domestic and family violence or any agreed recognition that its cause was a direct consequence of gender inequality and a direct cause of future gender inequality.

In 1995, the Fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing, the culmination of twenty years of work by the global women’s movement, and resulted in the Beijing Platform for Action.

The platform proved to be one of the most influential international policy documents regarding women’s human rights. Violence against women was one of twelve critical areas of concern.

Australia, one of the original signatories, continues to play a central role in international fora led by women’s specialist services representatives. Many feminists within and outside of government have taken their voices to the United Nations for years.

WESNET has used the United Nations Commission for the Status of Women (UNCSW) as a platform to raise the issues of technology-facilitated abuse and the importance of strengthening the presence of specialist women’s services. We also promoted the good work that Australia was doing so that we would not lose our progress. In 2019, for example, Margaret Augerinos, CEO of the Centre of Non-Violence and WESNET Board member, and I presented at parallel events to the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW63) entitled “Australian Women’s Shelters Filling Essential Services Gap”, “Specialist Women’s Services Against Violence as Essential Infrastructure”, and “Developing and Enhancing Coordinated Community Responses”.

National approaches

On the back of the Beijing Platform for Action, in November 1997, all Australian Heads of Government came together in a united effort to address domestic violence at the National Domestic Violence Summit. The Partnerships Against Domestic Violence (PADV) was formed.

This was followed in 2008 by the establishment of the National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (the National Council) and the first National Plan in 2012.

Although the first national plan was a significant achievement – and key steps forward were made, such as setting up a national research agenda, strengthening data collection, and putting prevention as a primary goal – there was little if any demonstrable progress towards ending violence.

Although women’s services attempted to influence the implementation of that National Plan it was very difficult to get governments to understand, let alone undertake the systemic and structural approach that needed to happen.

Throughout 2015 and 2016, I was a member of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Advisory Panel on Reducing Violence Against Women and their Children. (5) The panel, chaired by Ken Lay and Rosie Batty, made 28 recommendations in their report to COAG. The recommendations were across six themes:

- National leadership to challenge gender inequality and transform community attitudes

- Empowering women who experience violence to make informed choices

- Recognising children and young people as victims of violence against women

- Holding perpetrators to account for their actions and supporting them to change

- Providing trauma-informed responses to violence for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

- Providing integrated responses to keep women and their children safe.

Despite agreeing to ‘consider’ the recommendations in the Third Action Plan of the National Plan, there was no official endorsement or commitment to implementing the 28 recommendations. This was a lost opportunity that sent our progress back years.

Ignoring some of the key points of advocacy by the women’s sector, the plan failed on a number of key counts.

It did not centre men’s violence against women as a consequence of gender inequality and the intersection of other inequalities or oppressions.

It largely focussed on domestic and family violence and ignored other forms of gender-based violence, the most noticeable being sexual violence.

It failed to take seriously ‘everyday sexism’ and misogyny entrenched in Australian male culture and perpetuated and reinforced through attitudes, beliefs, systems and institutions.

It failed to recognise the transformational structural social change that needed to occur and what was needed to invest in that.

It did not centre the voices and experiences of women’s specialist services or the voices and experiences of victim-survivors – the people and the services that know the most about how best to prevent and address violence against women.

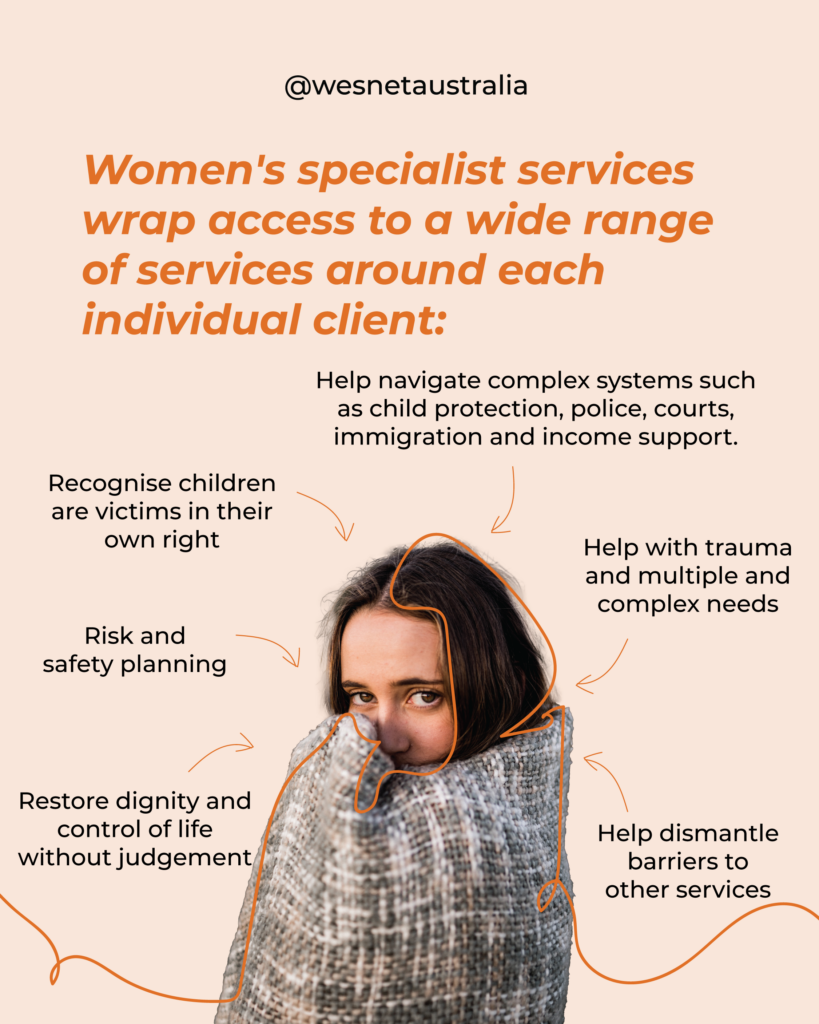

The other key policy failure has been the wresting of domestic and family services away from women’s specialist services and away from the very things that are known to best support women escaping violence: practices that are genuinely trauma-informed with a gender-lens and which seek to empower and build agency and capacity.

The new plan and the future

The new second National Plan to End Violence Against Women and Children gives hope.

The influence of women’s specialist services, including WESNET’s and feminist academics’ presence on the national advisory committee, is evident. This time we see victim-survivors, we see women’s specialist services, and we see the recognition of gender inequality and how it intersects with other social inequalities as the key driver of violence against women.

The prominence of intersectionality in the new plan is a key achievement, but this has to be understood in the context of how structural oppressions overlap and impact people rather than concentrate on diversity and barriers individuals and groups face. Transformational change will require the dismantling of these oppressive ideologies and structures.

We can say, finally, that the framework recognises that violence against women is a societal and community problem supported by oppressive and discriminatory systems and practices. We have finally named it, and now we can genuinely, with hope and continued advocacy, address it.

In giving effect to the plan we hope to see more. We especially want to see tangible recognition of the specialist women’s sector and its workforce in future funding decisions.

Non-specialist crisis support and accommodation might keep women and children safe in the short term – and it is certainly better than nothing – but it is just a short-term band-aid solution.

Women and children are empowered when they are helped to see that nothing they did or did not do was the problem. They are empowered when they understand that this is a structural systemic problem that is bigger than them as individuals. They are empowered when other women validate their experiences by understanding the nuanced way that male violence impacts them. Specialist women’s services must not be overlooked in the prevention space either.

Women’s specialist services – often on the back of lived experience – can lay claim to truly fighting for genuine gender and social equality and transformative structural social change. We look forward to strengthening specialist women’s services here in Australia and across the globe.

—

Footnotes:

- Jacqui Baker, ‘The fight for women’s refuge’, Overland, 2018.

- Catie Gilchrist, ‘Forty years of the Elsie Refuge for Women and Children’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Janet C. Bowstead, ‘Spaces of safety and more-than-safety in women’s refuges England’, Gender, Place & Culture, vol. 26, iss. 1, pp. 75-90, 2019.

- https://www.pmc.gov.au/resource-centre/office-women/coag-advisory-panel-reducing-violence-against-women-and-their-children