Speech presented by Julie Oberin AM.

“The Personal is Political”

Anyone around in the 1960s or 70s would associate ‘the Personal is the Political’ with the emboldened women’s liberation movement.

The rallying cry aimed to bridge the distinction between the gendered domains of private space – the home – for women. And the public sphere for men.

It also served to highlight the fundamental nature of the right to bodily autonomy, agency and self-determination.

Without control over their own bodies and selves, women were far less likely to be able to access broader legal, political and economic rights.

While reproductive rights spring immediately to mind – those relating to pregnancy and contraception – bodily autonomy encompasses a much broader suite of rights.

Personal agency includes the right to marry a person of your choice; or the right to control over your own earnings; or the right to decide freely when and with whom to have sex.

This is the essential philosophy that underscores the centrality of ‘consent’ to any discussion involving sexuality and violence against women.

Consent – and how it is defined and defended – goes to the heart of upholding women’s rights.

Legal framework and sexual violence

Laws have a role to play in both leading and reflecting the social climate of the time.

Sometimes they lead and create cultural change. Enabling women into spaces from where they were previously excluded, for example, changed many of those spaces.

Workplaces that once lawfully fired married women have, over time, become accommodating of workers’ caring responsibilities.

In other cases, laws lag. Criminalisation of rape in marriage in Australia began with New South Wales in 1981. It took over a decade for the final state to follow suit in 1992.

In the context of sexual violence, the legal approach to consent is evolving over time and, similarly to the way rape in marriage was treated, is at different stages in different parts of Australia.

While the definition of consent varies from state to state, the emphasis has been on when consent is not given or not obtainable, rather than when it is.

Consent may be deemed to be absent, for example, if the victim-survivor was asleep or unconscious. Complex considerations can exist around the accused’s ‘honest belief’.

Consent in legislation, like characteristics of many laws addressing crimes against women, has arguably favoured the more powerful.

This is starting to change, with the more balanced approach of ‘affirmative consent’.

The affirmative consent model is intended to circumvent some of the complexities and subjectivities associated with contemplation of the perpetrator’s beliefs and the victim’s behaviour.

Clearly, it is the behaviour of the perpetrator that should be the focus.

Until very recently Tasmania was the only jurisdiction to put the onus on both participants to ensure the other is actively consenting.

As many of you would be aware, the tenacity and bravery of young activist and victim-survivor Saxon Mullins has carried this issue into the public spotlight across the nation.

New South Wales

Two weeks ago (23 November 2021), New South Wales became the frontrunner on the mainland passing the affirmative consent bill, which requires people to expressly say or do something to confirm their partner consents to sexual activity.

The laws will also affirm a person’s right to withdraw consent at any point.

They make clear that if someone consents to one sexual act, it doesn’t mean they’ve consented to other sexual acts.

They will clarify that a defendant cannot rely on self-induced intoxication to show they were mistaken about consent.

Victoria

Victoria will be following suit shortly, with the introduction of their own affirmative consent provisions foreshadowed for 2022.

The Attorney-General Jaclyn Symes has said the changes will flip the system. Rather than focussing on the behaviour of victims, the perpetrator will need to describe actions taken to gain consent.

Other states

It is likely that other states will follow too.

Queensland has already modernised some aspects of consent – including enabling its withdrawal.

The Queensland Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce is examining whether further changes along an affirmative model are needed.

The ACT is currently reviewing its laws.

Internationally

While provisions vary within Australia, the range is wider internationally.

Sweden, Portugal, Spain and Denmark are considered most aligned to the affirmative consent model. Australia is largely on par with countries such as England, Wales, New Zealand and Canada.

According to an Amnesty report, only 12 of 31 European countries have a definition of rape that includes consent, with the others focussing on rape as by force or threat of force.

Worryingly, the report noted, some countries categorise sex without consent as a separate, lesser offence.

Amnesty notes that ‘consent-based definitions of rape and legal reforms are not the ultimate solutions to addressing and preventing this ever-present crime, rather they are significant starting points’.

Coercive control

Another dimension of consent that is currently receiving attention – again due largely to the activism of the sector and the bravery of victim-survivors such as Sue and Lloyd Clarke – is coercive control.

Coercive control is an umbrella term that refers to an ongoing pattern of controlling and coercive behaviours within a relationship or as a result of a former relationship.

It can include constant monitoring, isolation from friends and family, controlling access to money, and humiliation and threats.

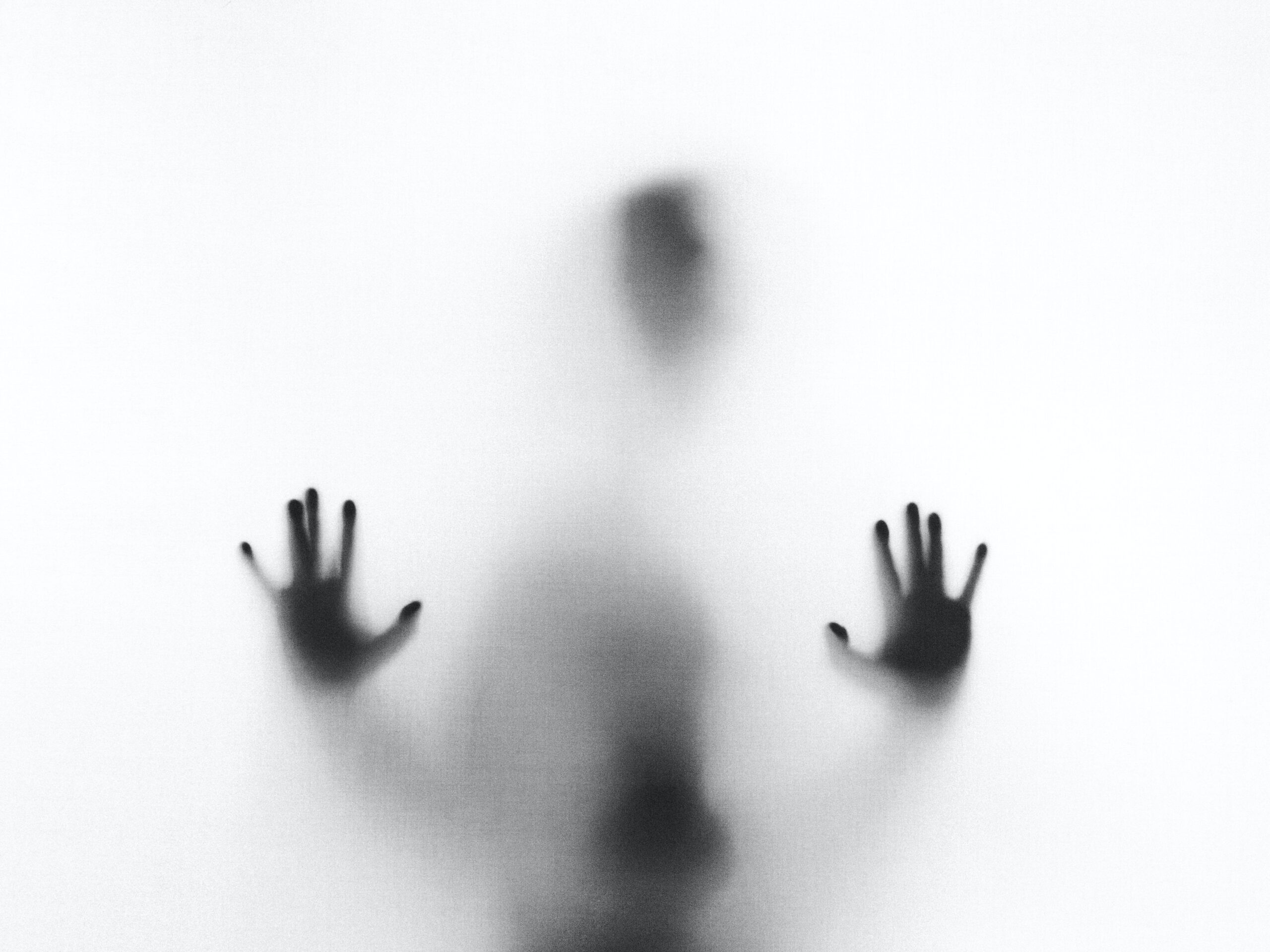

Coercive control is often so debilitating because it is so pervasive. Day by day a person’s rights are chipped away. The incremental advancement of control is almost imperceptible to the person living with it, day after day after day.

A key strategy of the coercive controller is to normalise abnormal demands and behaviours.

According to them, it is normal to share passwords. It is normal for men to manage the finances.

Good girlfriends tell their partners where they’re going. Good girlfriends give in to sexual demands.

The consequences of not being ‘normal’ or of not being ‘a good girlfriend’ also tend to escalate over time.

The erosion of rights makes it very difficult to identify the absence of consent.

For example, she may have agreed to give him her password. By the time she realised the full consequences of this she also understood the consequences of changing her password and denying him access.

Criminalisation

On its own, coercive control is not currently subject to criminal sanctions in most states and territories.

Only Tasmania explicitly criminalises non-physical forms of family violence such as economic abuse and emotional abuse or intimidation in their Family Violence Act.

Coercive control is recognised in the Victorian Family Violence Protection Act.

Bills have been introduced in New South Wales and South Australia.

The Queensland government will “extensively consider” the recommendations of the women’s safety task force calling for the criminalisation of coercive control.

Earlier this year (9 July 2021) a parliamentary committee recommended that federal and state governments develop shared principles to guide any criminalisation of coercive and controlling behaviour, with a view to ensuring consistency across jurisdictions.

These principles are currently in development.

The consultation process around the principles is raising some deeply held concerns around the criminalisation of coercive control.

There is a strong view that it could increase barriers for women who are already disadvantaged in accessing and navigating justice systems.

First Nations women fear reporting their experiences of violence because of the ongoing social and cultural marginalisation, racism, and lack of culturally sensitive services.

The extremely high rates of the removal of their children are a major disincentive to any engagement with the system (ANROWS, 2020).

Disability advocates have raised concerns that the pressure for carrying the burden of proof could become an adverse barrier for women with disability, especially for women with intellectual disabilities (DPOs Australia & NWA, 2019).

LGBTIQ+ people also feel that the police, justice system, and support services are not culturally safe (National LGBTI Health Alliance, 2020).

Refugee and migrant women may become targeted by their community if they involve the police.

Visa restrictions may render them unable to access social services without their spouse, and they may face systemic racism and xenophobia (Maturi & Munro, 2020).

These communities make clear the limitations of the legal system, particularly for vulnerable women.

Inherent biases are so deeply entrenched within the system – and within the people within the system – that the institutions and people entrusted to protect us can work instead to expose us to greater harm.

There is no quick fix legal solution to solving violence against women.

Without question we want perpetrators to be held to account and we want justice for victim-survivors. This is vitally important.

But it is equally essential that the full consequences are explored with victim-survivors. And that legal measures are not viewed in isolation from all the enabling structures such as policing and social services.

Culture and men’s entitlement

With the limitations of the legal system in full sight, and as it scrambles to keep up with emerging forms of violence against women, we need to be looking at all the levers we have available to try and effect change.

One of these levers – and possibly the most important one of all – is embedding the concept of consent at the very earliest opportunity, and at every available opportunity.

In a recent article in The Age, Kerri Sackville likens Tim Paine – the former Australian cricket captain – and his ‘dick pics’ to a toddler having inexplicable pride in his penis.

She concludes that dick pics are an inevitable consequence of male entitlement.

Some men – inflated with a sense of their own importance, and of the importance of their own penis – fail to understand that women do not want to see it. In their minds, dick pics are a gift…even if often a misunderstood one.

Their narcissism and entitlement blinds them to the need for consent.

In the alternative scenario, men weaponise their penises. A dick pic is a malevolent reminder of men’s capacity for sexual violence. They are intended to make the recipient feel disrespected and powerless.

Consent is willfully and deliberately ignored.

Non-consensual touching

Not all expressions of male entitlement and ignorance of consent are sexual.

Indeed, the foundations of consent are rooted in early childhood, long before the typical period of sexual activity.

Children are routinely touched – often in kind ways – by teachers, sports coaches, friends’ parents, neighbours. This can serve to blur the boundary between safe and unsafe touch, or consent versus coercion.

Children’s bodies are often treated as the property of their parents or other adults.

Helping children practice bodily autonomy is a critical starting point in the foundation of consent culture. It will help them understand the difference between appropriate and inappropriate touch.

As a community, we need to start using the language of consent – with children and between adults – and thinking about the concept of consent in all our day to day activities.

Men – particularly – need to understand that touch is rarely benign or welcome. It is a rare instance that touch – without consent – would be appropriate in the case of a work colleague, acquaintance or stranger.

Indeed, touch within relationships is not always innocuous or appreciated either.

We know that some women feel particularly vulnerable to unwelcome touching, not just by men.

Pregnant women speak regularly of pregnant tummies seemingly becoming public property.

People with disabilities talk about being routinely manhandled by people taking charge of mobility aids or touching or grabbing without consent.

Not just about touch

Consent is a cornerstone not just of our approach to touching – sexual and non-sexual – but also in how we treat people’s rights to bodily representation and privacy.

Image-based abuse is one of the most insidious forms of violence against women, emerging as a major issue in the last decade.

Intimate photographs are posted, uploaded, shared, and photoshopped.

While largely unlawful, it is a minefield in terms of consent, when photos may have been taken consensually or shared between intimate partners.

It becomes almost impossible to effectively withdraw the image from the public realm once it is out there.

With children’s access to phones and devices becoming an essential part of life and schooling, embedding consent education into early education settings once again becomes a critical intervention to address violence against women.

Being believed

Consent, bodily autonomy, agency and self-determination are the bedrock of human rights and should be part of the fabric of how we treat each other.

An important element of agency and self-determination is having a voice. Part of having a voice is being believed.

A recent report published by ANROWS found that as many as four in 10 Australians mistrust women’s reports of sexual violence.

This represents a massive hurdle to delivering agency and justice to women. We know that if a woman is disbelieved once, she is far less likely to come forward a second time.

A key finding by ANROWS was that ‘the sexual consent script needs to be changed from one where responsibility is on the woman to say “no” to one where consent involves both parties respectfully, continually and mutually agreeing to sex’.

Consent, again, is central.

Let her speak!

We have heard many wonderful young voices over the last year in Saxon, Brittany Higgins and Grace Tame. Their bravery cannot be understated.

But, as Saxon herself acknowledged, white able-bodied voices are more audible than those of First Nations women, women with disabilities, migrant and refugee women, older women, and people from the LGBTQI community.

While the broader public is starting to listen to some stories, it is important that more are heard. This is the road to understanding ways in which human rights breaches are experienced differently by women.

It is the road also to assuring women control over their own destinies; the ability to freely give or deny consent; and the space to speak and be heard.

If ‘the Personal is the Political’ was the clarion call for the 70s, this year’s “Let her speak” and “Enough!” reflect our focus for the years ahead.